In case you missed Part I, you can find it here.

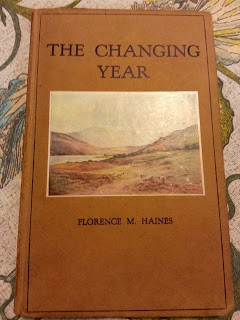

Since that post, I was able to obtain a copy of The Changing Year by F.M. Haines, the book mentioned by Charlotte Mason in Vol. 6 and her programmes as an aid to the “great deal of out-of-door work” her students did in a term.

From the Preface”

These papers originally appeared in The Parents’ Review of 1916 as a series of monthly Walks.

It is a beautiful book with 12 chapters “A Walk in January” “A Walk in February” “A Walk in March” etc. Each chapter describes what is observed as well as things like its behavior, some phenology and scientific knowledge, its Latin name and meaning of it, foreign names for it, any geographical and or economical tidbits relating to it, any fable, myth, historical knowledge about it, or bit of poetry relating to it.

It’s really not so much ‘scientific’ as it is all encompassing. The knowledge contained in these chapters was not compartmentalized information; it was holistic beyond the bounds of any one disjointed subject. Interestingly, it brings me right back to Charlotte and her idea that “education is the science of relations.”

In hopes of sharing the book with you, I searched the Redeemer site multiple ways upside and down to find the 1916 PR articles the book originated from, but came up empty handed.

Instead, I will post a few excerpts here to give you an idea, and perhaps at some point the entirety of the book can be shared online.

From the Chapter titled “A Walk in April”

In Yorkshire, Spring is said to have fully come when one can plant one’s foot upon nine Daisies, “those pearled arcturi of the earth” the Saxon daeges ege, eye of day, Chaucer’s “of all flouris the floure,” The scientific name, Bellis perennis, is from the Latin bellus, pretty, and the plant was so known in the time of Pliny; to the Italians it is pratolina, meadow flower, or Fiore di Primavera; to the French Marguerite, pearl; and to the Germans Gänselblumchen, little goose-flower, but also Tausendschönchen, a thousand prettinesses.

Beloved by poets and children, to the Scots it is the Bairnswort, bairn’s weed, and the Gowan of Burns and Hamilton. Sidney Dobell, in his charming Chanted Calendar, after likening the Primrose to a maiden watching a battle from a a tower, and the Wind-flower to one wounded and dishevelled “with purple streaks of woe,” says of the Daisies:

“Like a bannered show’s advance

While the crowd runs by the way,

With ten thousand flowers about them

They came trooping through the fields.

As a happy people come,

So came they.

As a happy people come

When the war has rolled away,

With dance and tabor, pipe and drum,

And all make holiday.

Then came the cowslip,

Like a dancer at the fair,

She spread her little mat of green,

And on it danced she.

With a fillet bound about her brow,

A fillet round her happy brow,

A golden fillet round her brow,

And rubies in her hair.”

These rubies are the “fairy favours” spoken of by Puck, the gift of the fairy queen. A country name for the Cowslip is “Fairy Cups,” and we know “When pattering raindrops begin to fall, tiny faces look wistfully through blades of grass for some friendly cowslip. In a moment little gossamer-robed forms are clambering up the stalks, rushing each one, into the nearest bell. Then comes a symphony of soft sweet voices, and he who listens may hear, perchance, a melody of Fairyland.”

From the Chapter titled “A Walk in November”

The Lark sings for the last time, occasionally a Thrush is heard, but the real November songster is the Robin Redbreast, Keble’s “sweet messenger of calm decay,” when

“Plaintively, in interrupted thrills

He sings the dirge of the departing year.”

Often the singer is one of the younger birds, who after their second moult, don the scarlet feathers of the adult and begin to practise their strains.

Now the Frog burrows into the mud at the bottom of the pond, Queen Wasps, Bees, and Ants are asleep, and Slugs and Snails retire to crevices. The November and the Winter Moth emerge from their cocoons, the former (Oporabia dilutata) is a woodland species, and may be seen resting on the under-surface of leaves, it measures about one and a half inches from wing to wing; the later (Cheimatobia brumata) is smaller than the November Moth and of a pale brown colour, the upper wings darker than the lower, the female has rudimentary wings; the larvae of this moth appear in May and are most destructive in orchards.

Now

“The early mornings have an aspect strange,

The day is breaking in a dense grey mist

That will not be dispersed. The fields are white,

And scarce a gleam of the uprising sun

Lights the dull landscape, E’en across the field

The trees are massed like fog-banks, in the hedge,

With ghostly vagueness. With his silver shields,

The Coltsfoot decks the bank. The garden plot

Shows every plant out-lined in purest white,

And the dark Gorse, in the pale morning beam,

Glistens as though with crystals.”

From the Chapter titled “A Walk in July”

July was originally named Quintilis, as being the fifth of the Roman year, but as “Caesar the Dictator was borne at Rome, when Caius Martius and Lucius and Valerius Flaccus were consols, vpon the fourth day before the Ides of Quintilis, this moneth after his deathe was, by vertue of the law Antonia, called, for that cause, Julie,” in honour of the Emperor whose labours had reformed the calendar, and whose birth-month it was. July is said to have been the first month of the Celtic year, and was known to the Anglo-Saxons as Hen Monath, or leaf month, from the Germain hain, a grove, and also Hew, or Hay, monat, mead month, the grass being now ripe in the meadows.

The Booke of Knowledge tells us that “Thunder in July signifieth the same year shall be good corn and loss of beasts if their strength shall perish,” a prophecy that, as far at least as the corn is concerned, is consolatory in a country whose summer is said to consist of “three hot days and a thunderstorm,” and it is curious that all through northern Europe certain days are set apart on which, if the rain falls, wet weather may be expected for some time after.

Sigh. I so much want to use this book. It is so great. We must be able to find the articles somewhere!